Post date:2017-03-10

1215

Visits With Master Craftspersons Down Quiet Lanes:

Using Stories to Awaken a City’s Memory

Article_Yeh Yawei

Photos_Lin Yanyi

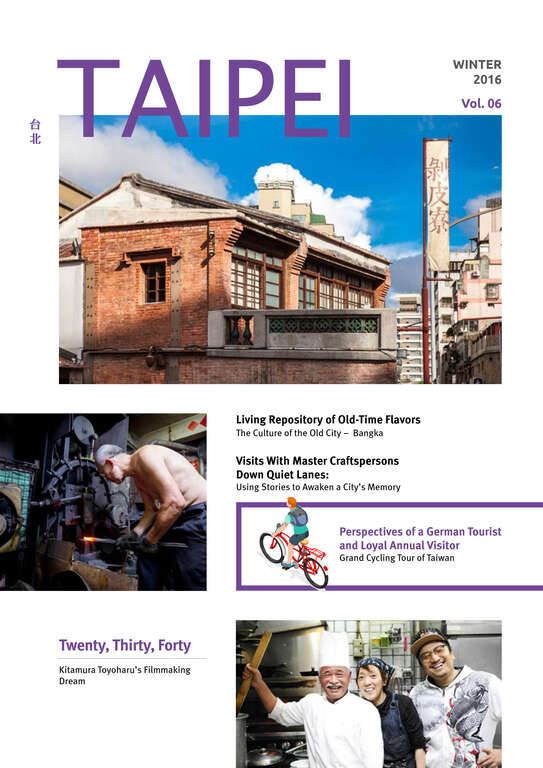

Wanhua was one of the earliest areas to develop in Taipei. Today, you’ll find concentrations of tea sellers, Chinese bakeries, Chinese herbal-medicine shops, clothing, clock, and watch wholesalers, and traditional blacksmith shops. From these old-time industries, so closely related to people’s daily lives, it’s easy to find traces of the lives of their ancestors as well. The community is a living landscape of master craftspersons and traditional skills passed on generation after generation.

Master A-Bao’s Curry Dumplings – An Old Bakery With Innovative New Tastes

“Master A-Bao’s Curry Dumplings” (阿寶師咖哩餃) was originally the “Fengmingxiang Food Shop” (鳳鳴香食品行). Second-generation proprietor Tang Kai (唐楷) inherited his craftsmanship from his father, Chen Jinbao (陳錦寶), who came to Taiwan in the Nationalist government exodus after the Chinese Civil War. Settling in Wanhua, he opened the Fengmingxiang Food Shop, choosing the name of his old business in Fuzhou (福州), mainland China. The main offerings were Fuzhou pastries and baked goods, such as jiguang buns (繼光餅), fried dough twist, and steamed spring roll, along with special seasonal offerings at Chinese New Year and Mid-Autumn Festival. In 1950, after taking over operations, Tang Kai began researching curry dumplings. Words spread quickly, and he decided to change the name to Master A-Bao’s Curry Dumplings. Sporting a different surname from his father, the latter marrying into his wife’s family and Tang taking his mother’s surname, Tang chose bao (寶; “treasure”) for the shop name so that following generations would continue to honor his father.

▲ The skin-oil crispiness/flakiness ratio is the key for Master A-Bao’s tasty curry dumplings. (Photo: Lin Yanyi)

▲ The skin-oil crispiness/flakiness ratio is the key for Master A-Bao’s tasty curry dumplings. (Photo: Lin Yanyi)

Tang says that the most important thing in hand-made Fuzhou pastries and baked goods is the degree of aged gluten used, which can be judged when kneading. “You can tell if there is enough gluten by the intensity of the sound when pounding the dough,” he says. In the past this was entirely dependent on the personal experience and skill of the master, but today machines can be used to measure the dough’s pH value. This can also be distinguished by checking the color of the dough during trial baking.

The shop’s curry dumplings, carefully pleated by hand, have a special shape. The ratio of oil-created crispiness/flakiness is also closely monitored, and is key to the texture and moistness. In business 70 years now, Tang still seeks to improve each and every day, and hopes that local industries will play an even deeper role in Wanhua’s future.

TaiHo Traditional Biscuit – Tastes That Bring Back Old Memories

Opened in 1946, TaiHo Traditional Biscuit (太和餅舖) was originally a grocery store. Third-generation manager Chen Junjie (陳俊傑) says that his grandfather once worked at the “Dahe Sugar Factory” (大和糖廠) in Taichung. In 1945, he returned to Taipei to open a shop with his siblings, calling it “A Little Bit More Than Dahe” (比大和多一點). Candied fruit, groceries, specialty goods, traditional Chinese cakes, and other items were sold. In the 1960s, flour from the United States began to be imported and baking courses offered. Chen’s father and uncles acquired new skills, and began hand-crafting baked goods. “Back then, baozi (包子; steamed meat-filled buns) and mantou (饅頭; steamed buns) were mainstream, but the new soft, puffy breads, filled with oils and sugar, proved very popular.” For the past two-plus decades, Chen and his family have been trying to reset the tone for this market segment. Presenting traditional Han pastries and baked goods as its signature offerings, TaiHo Traditional Biscuit has remained steadfast and true in preserving old-time flavors.

▲ Three generations of care and persistence are contained in each batch of traditional Chinese treats handmade using ancient methods. (Photo: Lin Yanyi)

Chen says that the preparations for Han pastries and baked goods are complex, and even the gathering together of ingredients takes significant time and effort. Using wintermelon meat cakes as example, the ingredients are wintermelon, nuts, lard, and milk powder. Time is first needed to soften the first two ingredients, so that they mix properly into the cake. “The ratio of the melon and minced meat and the proper cooking temperature are both key to bringing out the flavor. My hope is to bring out the flavors of childhood memories.” He recalls what his father used to say: “You have to make cakes and pastries you’d like to eat yourself; only these can be sold to your customers. In making cakes and pastries, you have to pass on a feeling of happiness to your buyers.” Continuing in the spirit of integrity, while, at the same time, willing to innovate, “baked cheese” (烤乳酪) treats have been rolled out in recent years. These have attracted young consumers, introducing them to the traditional and bringing a new stream of customers to the old shop.

San Xiu Blacksmith Shop – Family-Crafted Handmade Farm Implements

Once upon a time, Xichang Street (西昌街) in Wanhua District was renowned as a street where blacksmiths were concentrated. Today, the sole remaining blacksmith shop is “San Xiu Blacksmith Shop” (三秀打鐵店). Second-generation owner Zhang Rongxiu (張榮秀) recollects how his father and friends went into partnership to open the business way back in 1925, how the partnership was later dissolved, and how his father independently setting up San Xiu.”In its heyday, blacksmith shops lined Xichang Street from no. 2 to no. 26,” says Zhang. “We were the only clan to have three different enterprises. ‘Jin Sheng’ (金勝) which produced butchers’ knives, ‘Yuan Yi’ (元益) which made chefs’ knives, and San Xiu which crafted agricultural implements. They were highly skilled and worked quickly, and together formed a specialty source for myriad sorts of working tools.” The wide range and functional diversity of San Xiu’s products had a wide impact, the fact that blacksmith shops from as far away as the Jinshan and Hualien areas wanted to act as wholesalers serving as testament.

▲ Zhang Rongxiu says the glory days of blacksmiths may be past, but the noble spirit of the trade is immortal. (Photo: Lin Yanyi)

The techniques passed on to Zhang have their origin in the Huian (惠安) area of Fujian (福建) in mainland China.”Before doing any hammering, you have to work the scrap metal first and then heat the material to 1,300 degrees. After heating twice the metal is forged into shape. When hammering, red-hot sparks fly and the blacksmith’s hands get burned. Thus, the hands of a blacksmith are invariably covered with scars.” Today, machines have replaced traditional farm implements, and the 90-plus-year-old shop has turned to repairing construction equipment. The 70-year-old Zhang has no thoughts of retiring, however, and continues to put all his energies into preserving the blacksmith trade.

Fudatong Tea Shop – A Century of Expert Tea Roasting

Fudatong Tea Shop (福大同茶莊) has been a firsthand witness to the Taiwan tea industry and its ups and downs over its history of well over a century. Owner Cai Xuanfu (蔡玄甫) says that original settlers of Wanhua, formerly known as Bangka,

were from north Fujian. Tea was not yet grown in Taiwan, and they brought tea leaves via sailing ship from sellers in Xiamen (廈門). However, the tea often suffered moisture damage because transport took over one and a half month. After arrival in Bangka the leaves had to be cleaned and roasted before selling. In those days porters would wait for work in teahouses around today’s No. 2 Water Gate (二號水門), sipping tea and chatting, helping to form the tea culture of the common people. Kung Fu Tea (功夫茶) from Fujian’s Anxi (安溪) region was sold to the wealthy –

primarily Wuyi Narcissus (武夷水仙), Anxi Tieguanyin (安溪鐵觀音), and Lao Cong (老欉). “Storytelling teahouses” (說書茶館) also became a main attraction in the promotion of tea culture.

▲ Tea is no mere commodity; it is immersed in a long-standing culture, and tea with friends is the epitome of calm, contented happiness. (Photo: Lin Yanyi)

In the early days, tea was taken into the walled city for sale by porters using carrying poles. There were no tea shops; the function of chazhuang (茶莊; tea houses/manors) was solely to process tea. In the Hengyang Road (衡陽路), Bo’ai Road (博愛路), and Gongyuan Road (公園路) area, shops where today general merchandise, clothing, and jewelry are sold once housed tea sellers. Later, when Taiwan began growing its own tea, local chazhuang switched to developing floral teas. According to Cai, with good tea you cannot see flowers in the leaf, but a fresh and elegant floral fragrance wafts forth. Osmanthus flower from the city’s Nangang area and jasmine flower from its Luzhou area are used, with one layer of tea leaves and one layer of petals, with paper used for separation. With premium-quality teas, the stacks are left to mature for four days and nights, and referred to as “four flavors and four extractions” (四韻四提), and sometimes even “eight flavors and eight extractions” (八韻八提).

Longshan Buddhist Implements – Promoting the Art of Sculpture

Opened in 1895, “Longshan Buddhist Implements” (龍山佛具) has a long and illustrious history. Its Buddhist sculptures are known far and wide, with the store regularly visited by buyers from Buddhist implement shops and temples from as far afield as central and southern Taiwan, Penghu (澎湖), and Hualien.

▲ Longshan Buddhist Implements has a long and illustrious history. Its Buddhist sculptures are known far and wide. (Photo: Lin Yanyi)

Seventy-eight-year-old Li Ziyong (李子勇), from the sixth generation, is the current manager. Before the age of 20 he had already created two icons for the Longshan Temple, one of the Wei Tuo Bodhisattva (韋陀菩薩) and one of the Qie Lan Bodhisattva (伽藍菩薩). Speaking of Buddhist sculptures, he states: “The most difficult carving is the facial expression. Some people will study for over a decade and still not be able to capture the look of dignified, contemplative solemnity.”

Li adds that the process of making Buddhist statues is complicated. Ori-

ginally cotton-paper paste was used to mold the shape of the statue, later replaced with clay. Finally came the evolution of the tuotai (脫胎) or “bodiless” method, with clay used to mold the shape of the deity and then paper pasted on the surface. When the clay dries it is removed, like an embryo. The shell is then painted and the anjin (安金) process is carried out – the pasting on of a layer of gold foil – thereby completing a sturdy, artistic Buddhist statue. This method is still used today to create large statues, though with glass fiber used for the exterior instead. To satisfy people’s textural preferences, small and medium-sized statues are carved from wood.

The stock at Longshan Buddhist Implements goes far beyond what one might expect, appearing all-encompassing. Beyond the Chinese-style Buddhist icons, images of the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ can also be carved! “The industry for Buddhist implements will not decline,” says Li confidently, “because people will always worship. Just look, Buddhism is flourishing all over the world. A single center of worship can have over a million followers.”

Each city looks to create its own unique flavors as a mark of its identity. It explains who we are, and serves as a showcase of a city’s charms. Through the steadfast eyes of its expert craftspersons, the irreplaceable value of Wanhua is seen. The process of heritage transmission preserves the warmth of the old days, while at the same time being integrated with the thinking of a new era, leading Wanhua to new and

different heights.

Using Stories to Awaken a City’s Memory

Article_Yeh Yawei

Photos_Lin Yanyi

Wanhua was one of the earliest areas to develop in Taipei. Today, you’ll find concentrations of tea sellers, Chinese bakeries, Chinese herbal-medicine shops, clothing, clock, and watch wholesalers, and traditional blacksmith shops. From these old-time industries, so closely related to people’s daily lives, it’s easy to find traces of the lives of their ancestors as well. The community is a living landscape of master craftspersons and traditional skills passed on generation after generation.

Master A-Bao’s Curry Dumplings – An Old Bakery With Innovative New Tastes

“Master A-Bao’s Curry Dumplings” (阿寶師咖哩餃) was originally the “Fengmingxiang Food Shop” (鳳鳴香食品行). Second-generation proprietor Tang Kai (唐楷) inherited his craftsmanship from his father, Chen Jinbao (陳錦寶), who came to Taiwan in the Nationalist government exodus after the Chinese Civil War. Settling in Wanhua, he opened the Fengmingxiang Food Shop, choosing the name of his old business in Fuzhou (福州), mainland China. The main offerings were Fuzhou pastries and baked goods, such as jiguang buns (繼光餅), fried dough twist, and steamed spring roll, along with special seasonal offerings at Chinese New Year and Mid-Autumn Festival. In 1950, after taking over operations, Tang Kai began researching curry dumplings. Words spread quickly, and he decided to change the name to Master A-Bao’s Curry Dumplings. Sporting a different surname from his father, the latter marrying into his wife’s family and Tang taking his mother’s surname, Tang chose bao (寶; “treasure”) for the shop name so that following generations would continue to honor his father.

▲ The skin-oil crispiness/flakiness ratio is the key for Master A-Bao’s tasty curry dumplings. (Photo: Lin Yanyi)

▲ The skin-oil crispiness/flakiness ratio is the key for Master A-Bao’s tasty curry dumplings. (Photo: Lin Yanyi)Tang says that the most important thing in hand-made Fuzhou pastries and baked goods is the degree of aged gluten used, which can be judged when kneading. “You can tell if there is enough gluten by the intensity of the sound when pounding the dough,” he says. In the past this was entirely dependent on the personal experience and skill of the master, but today machines can be used to measure the dough’s pH value. This can also be distinguished by checking the color of the dough during trial baking.

The shop’s curry dumplings, carefully pleated by hand, have a special shape. The ratio of oil-created crispiness/flakiness is also closely monitored, and is key to the texture and moistness. In business 70 years now, Tang still seeks to improve each and every day, and hopes that local industries will play an even deeper role in Wanhua’s future.

TaiHo Traditional Biscuit – Tastes That Bring Back Old Memories

Opened in 1946, TaiHo Traditional Biscuit (太和餅舖) was originally a grocery store. Third-generation manager Chen Junjie (陳俊傑) says that his grandfather once worked at the “Dahe Sugar Factory” (大和糖廠) in Taichung. In 1945, he returned to Taipei to open a shop with his siblings, calling it “A Little Bit More Than Dahe” (比大和多一點). Candied fruit, groceries, specialty goods, traditional Chinese cakes, and other items were sold. In the 1960s, flour from the United States began to be imported and baking courses offered. Chen’s father and uncles acquired new skills, and began hand-crafting baked goods. “Back then, baozi (包子; steamed meat-filled buns) and mantou (饅頭; steamed buns) were mainstream, but the new soft, puffy breads, filled with oils and sugar, proved very popular.” For the past two-plus decades, Chen and his family have been trying to reset the tone for this market segment. Presenting traditional Han pastries and baked goods as its signature offerings, TaiHo Traditional Biscuit has remained steadfast and true in preserving old-time flavors.

▲ Three generations of care and persistence are contained in each batch of traditional Chinese treats handmade using ancient methods. (Photo: Lin Yanyi)

Chen says that the preparations for Han pastries and baked goods are complex, and even the gathering together of ingredients takes significant time and effort. Using wintermelon meat cakes as example, the ingredients are wintermelon, nuts, lard, and milk powder. Time is first needed to soften the first two ingredients, so that they mix properly into the cake. “The ratio of the melon and minced meat and the proper cooking temperature are both key to bringing out the flavor. My hope is to bring out the flavors of childhood memories.” He recalls what his father used to say: “You have to make cakes and pastries you’d like to eat yourself; only these can be sold to your customers. In making cakes and pastries, you have to pass on a feeling of happiness to your buyers.” Continuing in the spirit of integrity, while, at the same time, willing to innovate, “baked cheese” (烤乳酪) treats have been rolled out in recent years. These have attracted young consumers, introducing them to the traditional and bringing a new stream of customers to the old shop.

San Xiu Blacksmith Shop – Family-Crafted Handmade Farm Implements

Once upon a time, Xichang Street (西昌街) in Wanhua District was renowned as a street where blacksmiths were concentrated. Today, the sole remaining blacksmith shop is “San Xiu Blacksmith Shop” (三秀打鐵店). Second-generation owner Zhang Rongxiu (張榮秀) recollects how his father and friends went into partnership to open the business way back in 1925, how the partnership was later dissolved, and how his father independently setting up San Xiu.”In its heyday, blacksmith shops lined Xichang Street from no. 2 to no. 26,” says Zhang. “We were the only clan to have three different enterprises. ‘Jin Sheng’ (金勝) which produced butchers’ knives, ‘Yuan Yi’ (元益) which made chefs’ knives, and San Xiu which crafted agricultural implements. They were highly skilled and worked quickly, and together formed a specialty source for myriad sorts of working tools.” The wide range and functional diversity of San Xiu’s products had a wide impact, the fact that blacksmith shops from as far away as the Jinshan and Hualien areas wanted to act as wholesalers serving as testament.

▲ Zhang Rongxiu says the glory days of blacksmiths may be past, but the noble spirit of the trade is immortal. (Photo: Lin Yanyi)

The techniques passed on to Zhang have their origin in the Huian (惠安) area of Fujian (福建) in mainland China.”Before doing any hammering, you have to work the scrap metal first and then heat the material to 1,300 degrees. After heating twice the metal is forged into shape. When hammering, red-hot sparks fly and the blacksmith’s hands get burned. Thus, the hands of a blacksmith are invariably covered with scars.” Today, machines have replaced traditional farm implements, and the 90-plus-year-old shop has turned to repairing construction equipment. The 70-year-old Zhang has no thoughts of retiring, however, and continues to put all his energies into preserving the blacksmith trade.

Fudatong Tea Shop – A Century of Expert Tea Roasting

Fudatong Tea Shop (福大同茶莊) has been a firsthand witness to the Taiwan tea industry and its ups and downs over its history of well over a century. Owner Cai Xuanfu (蔡玄甫) says that original settlers of Wanhua, formerly known as Bangka,

were from north Fujian. Tea was not yet grown in Taiwan, and they brought tea leaves via sailing ship from sellers in Xiamen (廈門). However, the tea often suffered moisture damage because transport took over one and a half month. After arrival in Bangka the leaves had to be cleaned and roasted before selling. In those days porters would wait for work in teahouses around today’s No. 2 Water Gate (二號水門), sipping tea and chatting, helping to form the tea culture of the common people. Kung Fu Tea (功夫茶) from Fujian’s Anxi (安溪) region was sold to the wealthy –

primarily Wuyi Narcissus (武夷水仙), Anxi Tieguanyin (安溪鐵觀音), and Lao Cong (老欉). “Storytelling teahouses” (說書茶館) also became a main attraction in the promotion of tea culture.

▲ Tea is no mere commodity; it is immersed in a long-standing culture, and tea with friends is the epitome of calm, contented happiness. (Photo: Lin Yanyi)

In the early days, tea was taken into the walled city for sale by porters using carrying poles. There were no tea shops; the function of chazhuang (茶莊; tea houses/manors) was solely to process tea. In the Hengyang Road (衡陽路), Bo’ai Road (博愛路), and Gongyuan Road (公園路) area, shops where today general merchandise, clothing, and jewelry are sold once housed tea sellers. Later, when Taiwan began growing its own tea, local chazhuang switched to developing floral teas. According to Cai, with good tea you cannot see flowers in the leaf, but a fresh and elegant floral fragrance wafts forth. Osmanthus flower from the city’s Nangang area and jasmine flower from its Luzhou area are used, with one layer of tea leaves and one layer of petals, with paper used for separation. With premium-quality teas, the stacks are left to mature for four days and nights, and referred to as “four flavors and four extractions” (四韻四提), and sometimes even “eight flavors and eight extractions” (八韻八提).

Longshan Buddhist Implements – Promoting the Art of Sculpture

Opened in 1895, “Longshan Buddhist Implements” (龍山佛具) has a long and illustrious history. Its Buddhist sculptures are known far and wide, with the store regularly visited by buyers from Buddhist implement shops and temples from as far afield as central and southern Taiwan, Penghu (澎湖), and Hualien.

▲ Longshan Buddhist Implements has a long and illustrious history. Its Buddhist sculptures are known far and wide. (Photo: Lin Yanyi)

Seventy-eight-year-old Li Ziyong (李子勇), from the sixth generation, is the current manager. Before the age of 20 he had already created two icons for the Longshan Temple, one of the Wei Tuo Bodhisattva (韋陀菩薩) and one of the Qie Lan Bodhisattva (伽藍菩薩). Speaking of Buddhist sculptures, he states: “The most difficult carving is the facial expression. Some people will study for over a decade and still not be able to capture the look of dignified, contemplative solemnity.”

Li adds that the process of making Buddhist statues is complicated. Ori-

ginally cotton-paper paste was used to mold the shape of the statue, later replaced with clay. Finally came the evolution of the tuotai (脫胎) or “bodiless” method, with clay used to mold the shape of the deity and then paper pasted on the surface. When the clay dries it is removed, like an embryo. The shell is then painted and the anjin (安金) process is carried out – the pasting on of a layer of gold foil – thereby completing a sturdy, artistic Buddhist statue. This method is still used today to create large statues, though with glass fiber used for the exterior instead. To satisfy people’s textural preferences, small and medium-sized statues are carved from wood.

The stock at Longshan Buddhist Implements goes far beyond what one might expect, appearing all-encompassing. Beyond the Chinese-style Buddhist icons, images of the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ can also be carved! “The industry for Buddhist implements will not decline,” says Li confidently, “because people will always worship. Just look, Buddhism is flourishing all over the world. A single center of worship can have over a million followers.”

Each city looks to create its own unique flavors as a mark of its identity. It explains who we are, and serves as a showcase of a city’s charms. Through the steadfast eyes of its expert craftspersons, the irreplaceable value of Wanhua is seen. The process of heritage transmission preserves the warmth of the old days, while at the same time being integrated with the thinking of a new era, leading Wanhua to new and

different heights.

Gallery

:::

Popular articles

TAIPEI QUARTERLY 2016 WINTER Vol.06

TAIPEI QUARTERLY 2016 WINTER Vol.06 Women’s Volleyball Super-Spiker Wang Sin-Ting (TAIPEI QUARTERLY 2016 WINTER Vol.06)

Women’s Volleyball Super-Spiker Wang Sin-Ting (TAIPEI QUARTERLY 2016 WINTER Vol.06) Paiwan Skating ‘God of War’ Sung Ching-Yang (TAIPEI QUARTERLY 2016 WINTER Vol.06)

Paiwan Skating ‘God of War’ Sung Ching-Yang (TAIPEI QUARTERLY 2016 WINTER Vol.06) A literary World Flow Tour of Taipei-A Look at the Old City’s Elegance (TAIPEI QUARTERLY 2016 WINTER Vol.06)

A literary World Flow Tour of Taipei-A Look at the Old City’s Elegance (TAIPEI QUARTERLY 2016 WINTER Vol.06) The Culture of the Old City – Bangka (TAIPEI QUARTERLY 2016 WINTER Vol.06)

The Culture of the Old City – Bangka (TAIPEI QUARTERLY 2016 WINTER Vol.06) The Rise of Post-Youth Culture and Creativity Arts Pilgrimage – Ximending (TAIPEI QUARTERLY 2016 WINTER Vol.06)

The Rise of Post-Youth Culture and Creativity Arts Pilgrimage – Ximending (TAIPEI QUARTERLY 2016 WINTER Vol.06)

Visits With Master Craftspersons Down Quiet Lanes: Using Stories to Awaken a City’s Memory (TAIPEI QUARTERLY 2016 WINTER Vol.06)

Visits With Master Craftspersons Down Quiet Lanes: Using Stories to Awaken a City’s Memory (TAIPEI QUARTERLY 2016 WINTER Vol.06)